Boris Johnson told MPs on Monday that he had “no alternative” but to order a second lockdown in England to prevent coronavirus deaths being twice as bad this winter as they were in the spring.

But MPs and experts disagree over the rationale for the new measures, with differences over the Covid-19 numbers and their interpretation inevitable when, like economic statistics, none of the data is measured perfectly and much of it is already out of date.

This means the emerging evidence for the severity of the second wave is inconclusive, but there are five reasons to suggest that this autumn’s lockdown measures are taking place earlier in the upswing of Covid-19 than in March, and are likely to cause less economic pain.

The level of Covid-19 infections is high, but likely to be lower than in March

In the week to November 2, an average of 22,739 people in the UK tested positive for Covid-19 each day. But counting the number of positive cases generally gives low results because not everyone takes a test and many are asymptomatic.

In the week ending October 23, the random testing survey undertaken by the Office for National Statistics estimated there were around 51,900 daily infections in England alone, with a plausible range spanning between 38,500 and 79,200. Half of these cases were people showing no symptoms of the disease.

The Covid symptom study run by King’s College London estimates the number of infections in the UK is running between approximately 40,000 and 45,000 a day, while the latest survey from Imperial College London suggested there were 96,000 new infections per day in England between October 16 and 25.

All of these figures are significantly higher than the daily number of positive tests, but, as Tim Spector, professor of genetic epidemiology at King's College, said, recent data suggested that “cases have not spiralled out of control”.

The rate of daily infections is also much lower than estimates of the number in March around the time of the original lockdown. Then, estimates from both Cambridge university and Imperial College suggested there were between 300,000 and 400,000 per day.

Care is needed interpreting data on hospitalisations and deaths

New Covid-19 hospitalisations in England reached 1,345 in England last Thursday, a figure higher than the 1,128 total on March 23 when Mr Johnson announced the original lockdown.

But admissions were doubling in less than a week in late March, while they have been doubling at half that rate in October. In the first wave, medical staff also operated a strict triage tool, limiting care for some of the most vulnerable. There has been easier access to care so far this autumn.

Death rates also show very different trends compared with the spring. At the peak of the first wave, deaths in excess of the national average were twice the recorded number of daily Covid-19 deaths. In the second wave so far, excess deaths have been roughly the same.

There is evidence the UK’s second Covid-19 wave is already slowing

The number of cases, hospitalisations and deaths is still rising, but there is evidence emerging that the growth rate of the virus is already slowing.

Government scientists estimate the reproduction number — the number of people infected by each person with coronavirus — is between 1.1 and 1.3 across the UK. This means the virus is still growing. But the R-number has declined from a peak of between 1.4 and 1.6 at the start of October just after university terms began.

Positive cases have begun to decline in some of the worst-hit areas of the UK — the north-east of England, the Liverpool city region and student towns. This suggests there is significantly less additional action needed to see case numbers decline than in the spring.

Oliver Johnson, director of the Institute for Statistical Science at Bristol University, said: “It's not that things have got worse, it's that they haven't got better as much as we'd hoped current measures would achieve”.

Epidemiologists disagree about the likely spread of the second wave

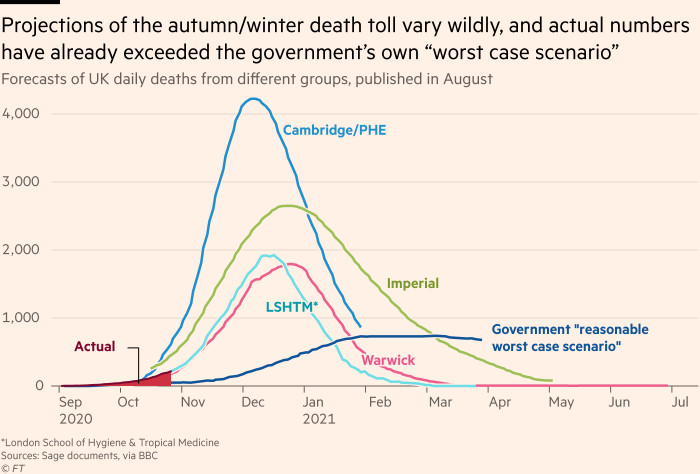

The second wave has been more serious than the government’s “reasonable worst-case scenario” because the effect of restrictions in stopping the spread of coronavirus has been modest so far.

This bad news does not mean that epidemiologists agree on the likely number of cases and deaths from a second wave. In a feature well known to economists, who also deal with uncertain data and human behaviour, forecasts vary a lot.

Prof Carl Heneghan of Oxford university, for example, on Monday criticised a model used by the government to justify the second lockdown that suggested deaths could peak at 4,000 a day, saying more recent data proved it was already “invalid”. However, Prof Neil Ferguson of Imperial College countered that the model was intended as a worst-case scenario and insisted that on current trends “the second wave is set to exceed the first wave in hospital demand and deaths”.

Prof Ferguson’s comment was based on the R-number remaining higher than 1. If the lockdown swiftly brings it below 1, it is highly unlikely the UK will suffer the 67,000 excess deaths that were recorded in the spring.

The economic consequences of a second lockdown appear less painful than the first

With UK gross domestic product plunging 19.8 per cent in the second quarter, and likely to perform worse in 2020 than in any year for more than a century, there are significant fears about a second lockdown.

Economists think the effects will be serious but far less damaging than in the first wave — or than if nothing was done to tame the virus. Some activity, such as public transport use, has not come back since the spring, while the government is actively seeking to keep sectors such as construction, education and manufacturing operating during the second lockdown.

With hopes that the restrictions will end in December, consumers are more likely to postpone rather than cancel spending plans. Compared with the huge drop in the second quarter, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research forecast a 3.3 per cent hit to GDP in the fourth quarter.

Hande Kucuk, NIESR deputy director, said while the situation was uncertain and the lockdown had caused the institute to cut its forecasts, the outlook “depends critically on whether we win the fight against Covid-19”.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50LzQ0NjEyNGNiLTE3ZWEtNDkxMy1hMGFkLWZjMjIzMGRjNjRlY9IBP2h0dHBzOi8vYW1wLmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50LzQ0NjEyNGNiLTE3ZWEtNDkxMy1hMGFkLWZjMjIzMGRjNjRlYw?oc=5

2020-11-03 04:01:16Z

52781155967431

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar