Phoenix Suns basketball star Chris Paul, UK health secretary Sajid Javid and US Olympic gymnast Kara Eaker have something in common: they have all tested positive for coronavirus despite being fully vaccinated.

No vaccine is 100 per cent effective, so what scientists call “breakthrough infections” were always expected. In most cases, the symptoms are mild.

However, as a new surge in Covid-19 cases has collided with a global vaccination campaign delivering more than 200m shots a week, more people are asking: “How protected am I?”

How many fully vaccinated people are testing positive?

While anecdotal accounts of breakthrough infections can make such cases feel widespread, the real numbers have remained small and were generally in line with expectations, experts said.

“There’s no such thing as a perfect vaccine . . . with Covid it’s no different,” said Professor William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University.

The yellow fever jab, for example, is widely understood to be the most effective live-virus vaccine ever invented, with a single dose generating long-lasting immunity in 98 per cent of those vaccinated. But even that means that on average 2 per cent of people will still get infected.

Phase 3 trials for most of the leading Covid-19 jabs showed an efficacy against symptomatic infection of more than 90 per cent. Real-world studies of effectiveness in the UK, Israel and Canada suggest that vaccines are displaying a slightly lower effectiveness outside of the trial environment, probably because of the spread of the more vaccine-resistant Delta variant. Estimates put protection against symptomatic infection, depending on the vaccine, at between 60-90 per cent.

According to Public Health England, about 17 per cent of the 105,598 Delta variant cases reported across England in the four weeks to July 19 were among fully vaccinated people. PHE counts people as fully vaccinated 14 days after their second dose.

Anthony Masters, a member of the UK’s Royal Statistical Society, said fully vaccinated people were likely to make up a “bigger proportion” of cases as vaccine coverage was extended, particularly in younger groups who face a higher exposure risk because of greater social mixing.

“If you get extremely high coverage across the different ages, it’s plausible that cases could become [in] majority among fully vaccinated people,” he said. About 55 per cent of the UK population had received both doses by July 21.

In Israel, where nearly 60 per cent of the population are fully vaccinated and coverage is spread more evenly across age cohorts, 52 per cent of around 6,000 people who tested positive in the week to July 21 were fully vaccinated.

Are some fully vaccinated people at more risk of falling ill than others?

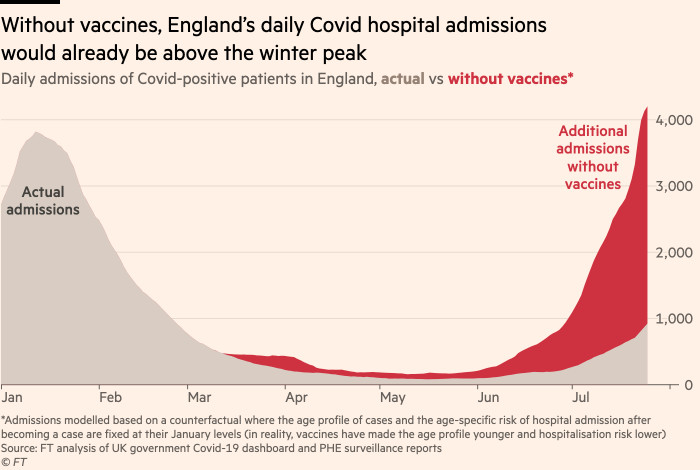

Very few fully vaccinated people who test positive for Covid-19 are getting seriously ill. According to PHE’s real-world studies, the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine is still 96 per cent effective against hospitalisation, while the Oxford/AstraZeneca shot is 92 per cent effective.

But Natalie Dean, a biostatistics professor at Emory University in Atlanta, stressed that these figures were averages and that efficacy depended on people’s existing risk profiles. “Everything is relative when it comes to vaccines and risk,” she said.

A Financial Times analysis of global infection fatality rates, for example, suggests that a double-jabbed 80-year-old now faces about the same mortality risk as an unvaccinated 50-year-old.

In England, where the vaccine rollout has been staggered from oldest to youngest and nine in 10 over-50s have been fully vaccinated, 30 per cent of the 1,788 people admitted to hospital due to the Delta variant in the four weeks to July 19 were fully vaccinated. About half of the 460 deaths in the country linked to the Delta strain since February were people who were also fully immunised.

“This is simply a reflection of vaccine uptake being very high among older people,” said Masters. “It’s perversely a marker of [a] successful rollout. If everyone [was] fully vaccinated, everyone who went to hospital or died would by definition be fully vaccinated.”

Around two-thirds of people who die on UK roads are wearing a seatbelt, but this is a consequence of usage rates of nearly 99 per cent, Masters said. He added that the same logic applied to severe disease and death in highly vaccinated populations.

Vanderbilt’s Schaffner added that people who experienced unpleasant but mild symptoms would probably have suffered severe disease, or even death, had they not been vaccinated. “Whenever my patients tell me they still had a mild illness despite vaccination, I always say I’m glad you’re still here to complain.”

Can you test how protected you are?

Not yet. The easiest way to understand how much immunity the vaccine has generated in a person is to measure the presence of neutralising antibodies in the blood. But T cells and B cells, which supplement the body’s immune system, also play a role and scientists remain unclear about which benchmarks offer the best insight into the vaccine’s effectiveness.

Commercially available antibody tests only show whether an individual has Covid-linked antibodies or not, but immunity is best understood as a “scale or continuum”, explained Danny Altmann, an immunology professor at Imperial College London. “It’s not binary. You’re not safe or unsafe, protected or not protected. People all have varying degrees of protection from the vaccine.”

This range of immunity can be plotted with a test called a neutralisation assay, which analyses how many times antibodies taken from the blood can be diluted in a laboratory and still neutralise the virus.

At the extremes, immunocompromised people may only generate enough antibodies to weather a 100-fold dilution, Altmann said. In comparison, healthy young people may have enough for a 10,000-fold dilution and are “likely impervious” to infection.

If scientists were able to establish the midpoint between the two extremes, Altmann said “vaccine makers would be able to update vaccines quicker for new variants and policymakers could better determine which people are in most need of booster doses.”

What do imperfect vaccines mean for herd immunity?

Kit Yates, a mathematical biologist at Bath university, warned that the imperfect protection offered by the vaccine against infection meant herd immunity could be “impossible” without vaccine uptake of above 90 per cent.

“Leaky vaccines probably put herd immunity out of reach, especially when faced with [the] Delta [variant],” he said.

Adam Kucharski, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said that with the UK anticipating in excess of 100,000 cases a day by late August, the implications of imperfect vaccines “will soon become clear”.

PHE estimates that on average the Covid-19 vaccines being used in the UK are between 91 and 97 per cent effective in preventing hospitalisation.

Kucharski warned that small differences could have a big effect on how much this wave of infections stretches the British healthcare system. “If you flip the number, you’re left with how ineffective the vaccines are and 9 per cent ineffective rather than 3 per cent ineffective means three times more hospitalisations.”

Adblock test (Why?)

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50LzBmMTFiMjE5LTBmMWItNDIwZS04MTg4LTY2NTFkMWU3NDlmZtIBP2h0dHBzOi8vYW1wLmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50LzBmMTFiMjE5LTBmMWItNDIwZS04MTg4LTY2NTFkMWU3NDlmZg?oc=5

2021-07-23 17:03:12Z

52781747649366